I learned lot from college students this week

With campus in chaos and students being attacked, it was good to meet a group of students that are too often ignored.

I’ve always believed that education is more than just a right—it’s a liberator, a ticket to the future. But let’s face it: our education system can feel like a factory, churning out students. Public schools do commendably with many kids, turning them into sharp, productive citizens. But for those who don’t fit the mold—struggling readers, English Language Learners, kids burdened with trauma—the system can be a ruthless grinder. It’s a tragedy, a colossal waste, like a farmer ripping out an excellent crop and tossing it by the wayside.

This was made clear to me this week. Jennifer Berkshire, a former adversary turned ally, invited me to speak to a group of college students at Boston College. Jennifer and I used to be on opposite sides of the education reform battle. She was a union loyalist; I was a reform zealot. We had plenty to fight about online.

But as the reform “movement” started to stray from its principles of justice and equity and veered into the murky waters of racist school choice agendas or weird fascination with robots, I began to see things differently. We were bitter enemies. We are now comrades in the fight for better education. That says a lot about humility, forgiveness, and the human capacity for growth—an apt metaphor for what education should ideally accomplish.

Jennifer had previously brought me to speak at Yale. Picture this: me, with my less-than-stellar education background, standing in the hallowed halls of an Ivy League school. My only frame of reference for these elite institutions was from bad 80s movies. The Yale students I spoke with were everything you’d hope for—thoughtful, prepared, sharp as tacks. They shattered the stereotype of today’s college students as overly sensitive and out-of-touch snowflakes. They were smarter and better behaved than their aging critics.

That said, my recent trip to speak with Boston College students was something else entirely.

Instead of delivering my usual spiel, I got to sit back and listen to the students. They delivered mini-TED talks that were raw, real, and profoundly moving. The master of the ceremony was a student nicknamed “the professor,” probably because of his above-average ability to understand and articulate the material we would hear.

One student talked about the overlooked contexts some kids grow up in—where resources are scarce, schools are failing, and the cracks kids fall through seem to grow wider by the day. He urged us to examine how school funding fails those who carry heavy social burdens from poverty and systemic neglect. His answer is to fill in the gaps with services that keep students afloat even as circumstances try to keep them down.

Another student gave a talk called “Insidious Pride.” He delved into how pride can drive us to do terrible things—to ourselves and others. He painted a vivid picture of how colonizers in Haiti abused their subjects to assert control and how that abuse was internalized and perpetuated across generations. Hurt people hurt others. Violence begets violence. The only way out is to acknowledge the toxic legacy of pride and to be self-reflective about our mental health.

Then there was the student who talked about how schools hobble young people. He argued that schools often fail to understand the unique needs and traumas of students from challenging backgrounds, clipping their wings early and setting them up for a lifetime of struggles.

One story that will stick with me came from a student who grew up in Tampico, Mexico. He described how schools there felt like a second home, where teachers cared deeply for their students. When he moved to the United States, he encountered a cold, indifferent teacher who was annoyed by his speaking Spanish. It was a harsh lesson for a young boy to learn. He could see how different and unwelcoming our schools can be.

The final student made a compelling case for schools designed explicitly for Black students. Before Brown v. Board 70 years ago, we had Black schools that were closing gaps between Black and white students. We had teachers that gave our students the Tampico experience. The student argued that Black children need environments that affirm their cultural identity and meet their unique needs, free from the low expectations and toxic norms of white-centered education systems. This hit home for me, aligning with my belief in reclaiming the Black mind and fostering academic success through culturally relevant education.

I got a little lost in the presentations. Lots of thoughts are going through my head about how important it is to listen more than we talk and to hear people we rarely hear or learn from. These students turned a light on for me that I didn’t know was off. Schooling about more than the three R’s. It is about human development, and humans are far more complex than their ability to read, count, and pass tests.

I was supposed to wrap up with some remarks about my own experiences in education policy battles, but time was short. Instead, I used my few minutes to tell the students how blown away I was by their brilliance and insights. Their talks were like gems, each a precious piece of wisdom to carry forward.

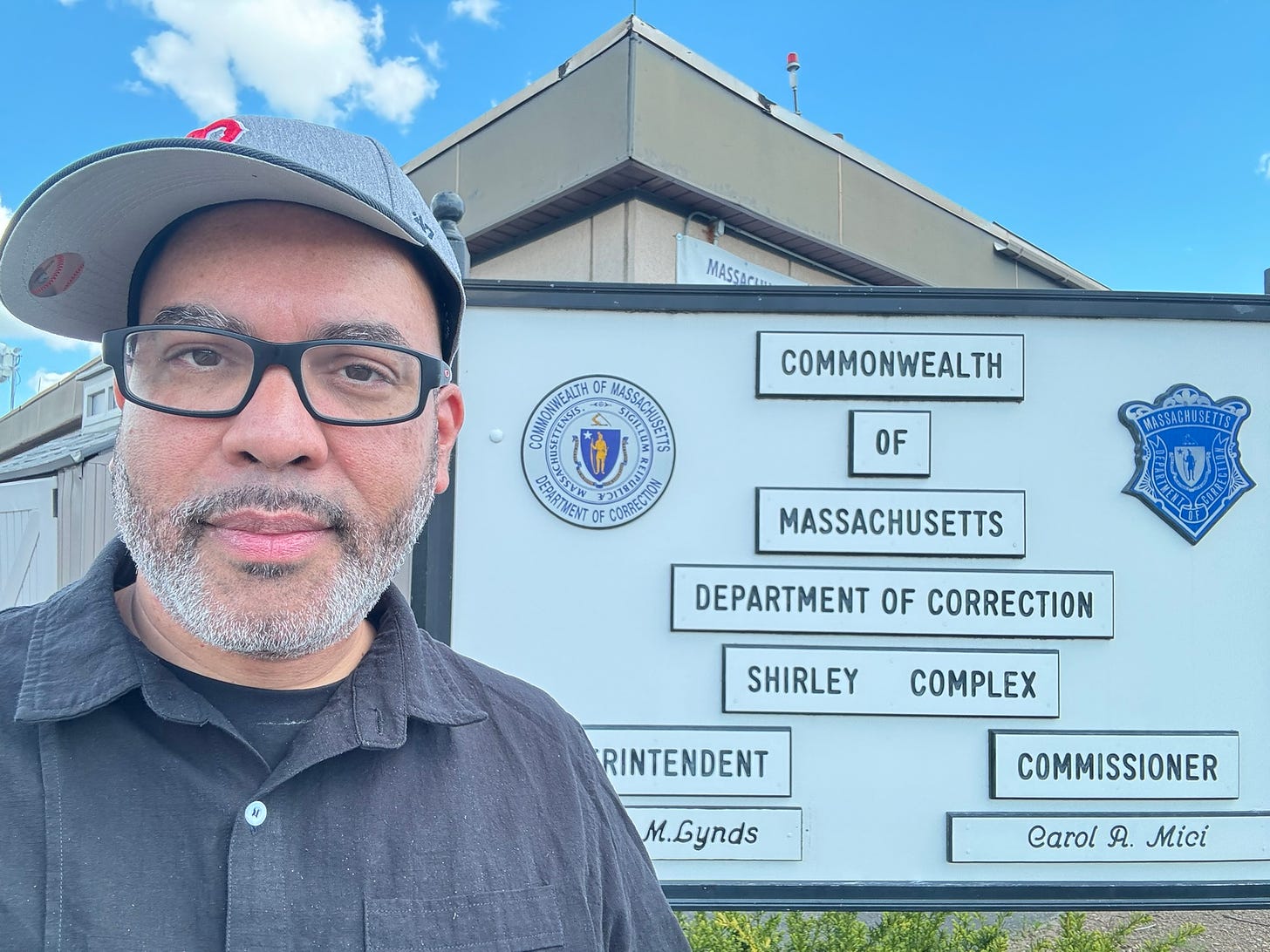

I left out one small detail until now: these students are inmates at the Shirley Complex of the Massachusetts Department of Corrections. I didn’t say that before because it's not the most important thing about them. Their wisdom matters. Their stories must be heard and understood. I heard them. I was moved. I wish the world could hear them, too.

Here I am outside of the facility:

When Jennifer drove me away from the prison, it hit me that when America incarcerates people, it isn’t just the body that is held captive. It’s their minds we lose. Their creativity, experience, and knowledge. The things we pretend they don’t have because admitting they are capable people is the first step to remembering that they are human.

And, as humans, they have an internationally recognized right to education and intellectual development whether they are incarcerated or not.

That Jennifer—Dr. Berkshire, as her students call her—is energized by teaching in a correctional facility gives her a new glow. It’s funny how wrong you can be about people when you’re dedicated to demonizing them. It’s even funnier to realize you have missed out on knowing a solid human.

I once accused her of being callous about the needs of Black students and of only seeing things through a white middle-class college-educated perspective. And here she is, trying to free the very people I care about and proving no one is disposable.

Not her, not me, and not the students she taught this semester.