Kids are being coddled. Except the ones who aren't.

Talk of 'saftyism,' lack of resilience, and pampered parenting is another example of the middle-class talking to itself.

Let's cut through the noise. You've heard the chatter, right? Pundits and armchair philosophers lament how today's youth can't handle a crossword without a safe space to run to. They spin tales of a generation so pampered, so wrapped in cotton wool, that a stiff breeze might knock them over. They blame smartphones, coddling parents, and schools turned into emotional day spas.

But here’s the raw truth, served straight up: this narrative is recklessly oversimplified, the intellectual equivalent of a misplaced road sign. It’s a one-size-fits-all story that doesn’t quite fit all.

Jonathan Haidt, the trendy conservative conch, is the drum major here. His books "The Coddling of the American Mind” and “The Anxious Generation” have whipped up fears about “safetyism” and students being too fragile to endure a harsh word.

My takeaway from Haidt’s writing and talks is that protecting students from offensive or discomforting ideas feels compassionate, but it’s not. It’s disabling.

That’s not unreasonable. I’m sure if I looked for that, I’d find it, especially on the most tony university campuses, where a critical mass of students don’t rely on work-study programs.

He talks about the “Three Great Untruths"—1) ideas that exposure to tough ideas is dangerous, 2) that we should always trust our feelings, and 3) that life is a battle between good people and evil ones.

And sure, toss in digital addictions to spice things up. Like video games, the internet, television, movies, music, radio, novels, dancing, and chess trap the youngins in an existential crisis.

What are the toxic byproducts of these dangerous activities? Social deprivation, sleep deprivation, attention fragmentation, and addiction.

It sounds compelling, maybe even logical, but resist easy answers if possible.

Smart critics of the anti-coddlers aren’t buying it, nor should you. Studies poke holes in Haidt’s theories, suggesting there's no clear, definitive link between digital depravity and the mental health of adolescents.

An Atlantic article challenges some of Haight’s theories with enough conviction to create doubt about his others.

In a review of 40 previous studies published in 2020, Odgers found no cause-effect relationship between smartphone ownership, social media usage and adolescents’ mental health. A 2023 analysis of wellbeing and Facebook adoption in 72 countries cited by Odgers delivered no evidence connecting the spread of social media with mental illness. (Those researchers even found that Facebook adoption predicted some positive trends in wellbeing among young people.) Another survey of more than 500 teens and over 1,000 undergraduates conducted over two and six years, respectively, found that increased social media use did not precede the onset of depression.

Some data even suggest that social media might be doing some good.

Imagine that.

Campus kids aren’t representative of young people

I believe with all my heart and very little evidence that middle-aged white academics posit the coddler myth so hard because their entire world is on campus. It’s their natural habitat. It may escape them that university students, especially the elite ones, aren’t representative of the entire generation. Only a good deal of social insulation and robust classism would imply that the pronoun posse in colleges is like the cadre of cousins they left behind on the streets with potholes.

Let’s talk about the kids who aren't invited to this pity party—the ones who don’t live in the leafy suburbs with helicopter parents and therapists on speed dial. I'm talking about the kids dodging bullets on their way to school, babysitting siblings instead of playing video games, and cooking dinner because mom's working two jobs and won’t be home 'til midnight.

These kids are dealing with real problems, not fretting over microaggressions. They’ve got grit in spades, born from necessity, not from a "grit curriculum" or some TED Talk spiel.

Among these overlooked young people, 5.4 million teenagers are tasked with in-home care for family members, often without the financial means for outside assistance. Additionally, 2.2 million of these teens are entrenched in poverty, with black teens disproportionately affected, being twice as likely to reside in households below the poverty line.

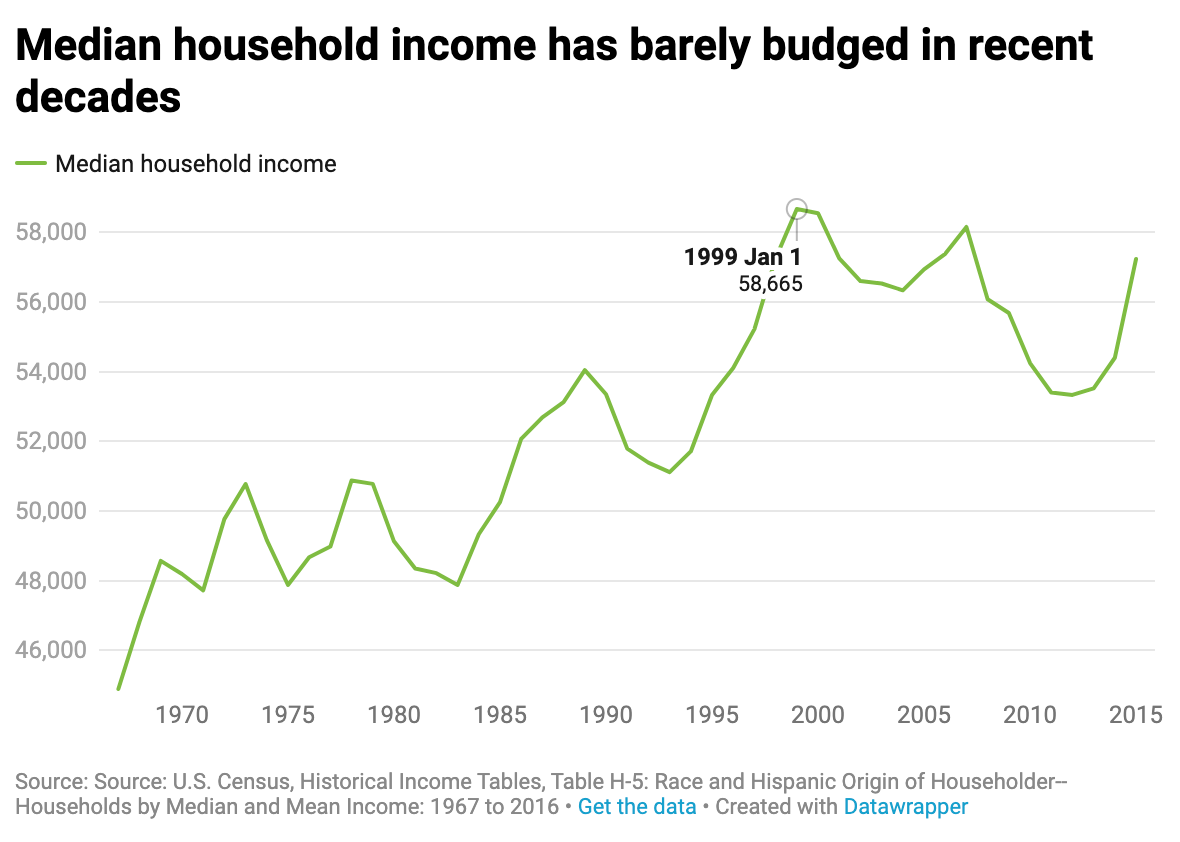

The Great Recession has left deep scars on many of their communities, representing the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression. During this period, families were stripped of jobs, homes, and stable incomes, with many assets devalued to worthlessness. From January 2007 to January 2012, the median income plummeted significantly, not once, but twice.

Consequently, the poverty rate escalated from 12.5 percent in 2007 to over 15 percent in 2010, underscoring the enduring challenges these young people face.

Our youth exist on different planes—split not by their resilience but by zip codes. While the well-off worry about their children's emotional fragility, others face a daily survival test that would break most adults.

Yes, they have cell phones. No, it isn’t giving them bulimia in the food deserts they live in.

The real crisis isn’t about our kids being too soft; it’s about a society quick to generalize and slow to understand. It’s about ignoring the tougher truths of inequality and adversity faced by those on the economic fringes.

So next time someone starts ranting about the coddled minds of our youth, ask them: Which kids are we talking about? Because it seems like a lot of them are fighting battles that would make the rest of us shart our briefs.

Snowflakes, indeed.