Years ago, I came to pick up my baby boy from preschool only to find him wearing a pilgrim’s hat. The teacher, an exceedingly nice, gentle, and loving Baptist evangelical who loved our kids like her own, had organized a cute Thanksgiving activity for the youngsters.

All of my militant internal alarms went off. It seemed like a huge breach of reason and an offensive cultural crime to dress my kid as a settler rather than the indigenous. Although multiracial, we are, after all, closer to Indian than white.

Even though I wanted to go to school with this teacher and ensure my child never again suffered that ignorance, I did nothing. There was no malice involved. Generation after generation -including mine, Gen X - have been steeped in myths that are hard to interrupt.

In truth, I would have had to school myself first. I only vaguely remembered learning alternative, meaning more factual details about Thanksgiving. I thought it was wrong for my baby boy to be a pilgrim, but I didn’t know why.

Another truth: though I was raised monoracially Black, and my kids are multiracially Black, Ancestry.com might tell you we are a combination of foundational American elements - African, European, and Indigenous.

So, it’s complicated.

Today, I’m grateful that we have the greatest access to information ever in human history. We have 24/7 Internet, libraries, and research at our command. This means we have all the tools we need to undue centuries of lies that hogtie us to the past even as we reach for a better future.

The Thanksgiving Myth

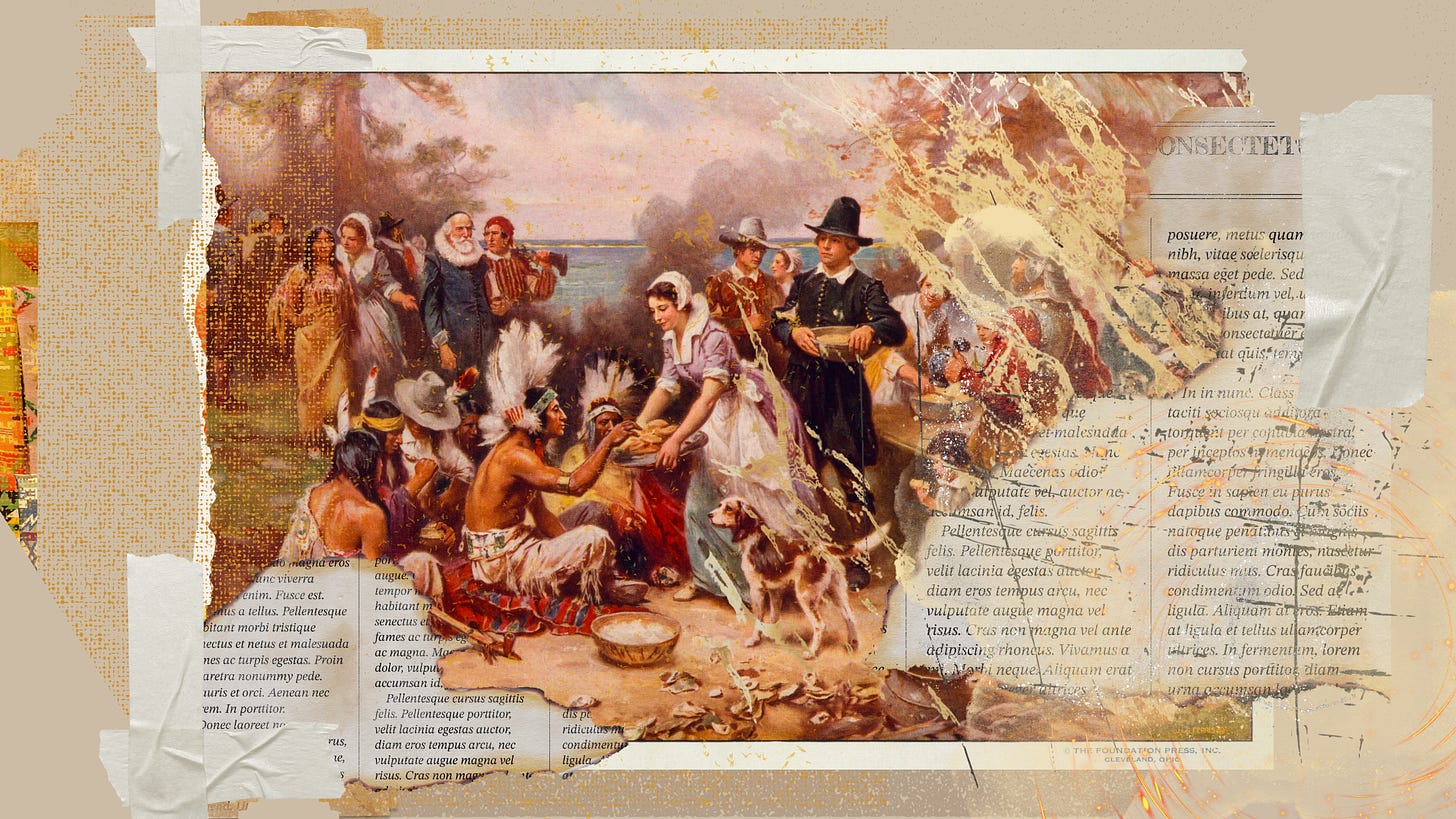

The shared story we tell about America’s founding and Thanksgiving is the one about English settlers seeking religious freedom, landing at Plymouth Rock, and forging a friendship with Native Americans like Squanto, culminating in the Thanksgiving feast. Historical records on the first Thanksgiving are scarce, and it took nearly three centuries to become a national holiday, but we have some clues that tell us our national recollection is a myth.

In the Crash Course video below, John Green examines the founding of America, debunking the myth that it was solely about religious freedom and highlighting the pursuit of economic gain. He explains how Jamestown, Virginia, became the first successful English colony, driven by the hope of finding gold but thriving through tobacco cultivation. The video also touches upon the differences between the Pilgrims and Puritans, emphasizing their religious beliefs and challenges in early America.

When he gets to Thanksgiving and the Pilgrims' arrival in Massachusetts, Green applies a critical lens to the traditional narrative. He hints at a more multifaceted historical context that goes beyond the celebratory "big feast," suggesting that Thanksgiving doesn't fully capture the intricacies of early American history, particularly in terms of indigenous and Spanish influences and the complexities surrounding the founding of the United States.

My summarizing won’t do it justice, so please watch for yourself:

Why not celebrate ‘Truthsgiving’?

So, if the current version of Thanksgiving is a mass delusion, what could we shift to that would be more than a day of stuffing our pie hole with stuffing and a whole lot of pie?

Enter Christine Nobiss, MA, who suggests we celebrate an alternative view she calls “Truthsgiving.”

In a Bustle article, “Thanksgiving Promotes Whitewashed History, So I Organized Truthsgiving Instead,” Nobiss addresses the problematic aspects of the Thanksgiving holiday and its deeply entrenched mythologies regarding Native Americans.

She also asks us to commit to a complete overhaul of Thanksgiving, similar to the revisioning of Columbus Day as Indigenous Peoples' Day, as a way to address the violent and whitewashed history underlying the holiday and promote truth-telling, healing, and reconciliation.

Our Thanksgiving myths provide cover for institutionalized racism and whitewash the historical reality of colonization, she says. Settler colonialism’s violent history, including grave injustices committed against Indigenous peoples, such as grave robbing and theft of their resources, is buried beneath the feel-good stories we tell ourselves.

Norbiss suggests that we do the following:

Focus on resistance efforts by Indigenous organizers to challenge damaging myths with events such as the National Day of Mourning and Indigenous Peoples' Day.

Educate ourselves and others about the true history of Thanksgiving.

Support Indigenous-led events and consider alternative celebrations that acknowledge past injustices.

Share educational resources and books like "Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years" to reexamine traditional narratives.

Discussing the importance of Indigenous foods and food sovereignty with children, providing a toolkit for combatting racism in schools regarding Thanksgiving activities.

History’s call for us to do better

All these years later, my pilgrim preschooler is now a tall, lanky, sharp-witted high schooler. I can’t say I’ve been a perfect teacher on these subjects, and I’m sure there are many historical blindspots in his and his siblings' education. I could give the excuse that life is busy, the hustle is real, our plates are full, and we can’t save the world all the time.

Everywhere we turn, there is a demand that we do better in understanding the past’s hold on today’s injustices. We are told to upset our norms and deconstruct everything we know. It’s disorienting, demanding, and frankly, tiring.

And yet, making wrong things right so that our future generations can have a world that works equally well for everyone is a mission worth the labor and inconvenience.

We carry a debt to those before us. Our lives are remarkably posh because of their pain. In that light, shifting from Thanksgiving to Truthsgiving isn’t the burden we might think it is.